Discovering Tilton, Part III of IV

- Typewriter Gazette

- Sep 2, 2024

- 20 min read

Updated: Sep 14, 2024

Mysteries Solved:

The Tilton Manufacturing Company

Charles E. Tilton, Inventor

Tilton and the World Typewriter

In Parts I and II of Discovering Tilton, you were introduced to the Tilton family and Elliott G. Thorp, and watched the growth of Fred and Elliott from druggists to stationers. You discovered that the factory in Boston at 50 Hartford & 113 Purchase Streets was built by the Thorp Mfg. Co., and was later purchased by the Thorp & Adams Mfg. Co., both while Elliott Thorp was the sitting treasurer. In the end, we had left Fred Tilton in 1887, after he had purchased and then left the “Old Merriam Bookstore”, after having suffered and recovered from financial difficulties. In Part III of Discovering Tilton, we will continue to follow Fred and Elliott into the solutions to the mysteries that instigated this body of research: what was the relationship between the Tilton Mfg. Co., the Tilton family, and Tilton, NH, who was Charles E. Tilton, and what was his relationship, if any, to the Tilton Mfg. Co. We will conclude Part III with the accidental resolution to another mystery uncovered while conducting this research: what were the links between the World typewriter and the star product of the Tilton Mfg. Co., the Victor index.

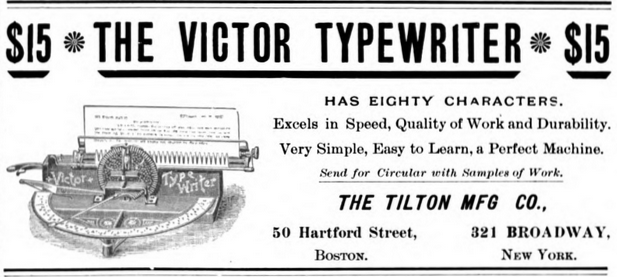

1888: The Birth of the Tilton Manufacturing Company

We find ourselves in 1888, the year that the Thorp & Adams Mfg. Co. was certified in Boston. It was in this year that the star of our story was finally born. On August 28, 1888, Tilton Mfg. Co. became a corporation of the state of Maine. The company’s stated purpose was to manufacture and sell all kinds of inventions, patents, and merchandise. With this new company, Dr. Thorp decided to take a more senior role as the company’s president. So who took the role of treasurer? Re-enter Mr. Fred G. Tilton of Boston, MA. They named two other directors, Orestes T. Doe and W. J. Knowlton, both from Maine (Worthington, 1888; New Corporations, 1888). And it seems that the cross-breeding of stationery companies followed these men. From Part II you know that Thorp & Adams Mfg. Co. located its factory at the old Thorp Mfg. Co., 113 Purchase & 50 Hartford (Boston Almanac, 1891, p. 212), with sales offices on Broadway, off Duane St., in New York. In January 1889, we find Tilton Mfg. Co. listed next door, at 115 Purchase St., and also at 91 Duane St., New York (Howard, n.d.; Sampson, Murdock & Co., 1889, p. 1248). They also had a PA presence, at 724 Chestnut St., Philadelphia (Howard, n.d.). By November 1890, a man named Arthur C. Harvey had moved his company into 115 Purchase, and we finally find Tilton Mfg. Co. at 113 Purchase & 50 Hartford, and also at 321 Broadway in New York (Howard, n.d.; Sampson, Murdock & Co., 1890). It seems that Tilton moved over to co-locate with Thorp's other business.

What I don't understand is, if Tilton Mfg. Co. and Thorp & Adams Mfg. Co. were both occupying the same and/ or adjoining buildings, if Thorp was a member of each, and if both were producing goods related to writing, why would Thorp keep these two businesses separate? One possibility could be that he wanted to specialize each company for a different purpose. Thorp & Adams Mfg. Co. was largely advertised as a general stationer, and Tilton Mfg. Co. was largely advertised as a typewriter business (Typewriters, 1890; Boston Almanac, 1891). Dr. Thorp may have been hedging his bets by separating out the nominal manufacturing businesses while making use of the shared factory, perhaps to save on overhead costs. Or perhaps his other business partners did not want to have anything to do with the typewriter market? If you consider the budding Personal Computer business of the 1970s, by the 1990s, if a small business tried to enter the market, they would have had to compete against the PC giant, IBM. While it could have been lucrative due to the size of the market, there was also a very big risk of sinking one’s business by trying to compete against a mature and established organization. The typewriter business shared a similar environment one hundred years earlier.

Possible motivation for business decisions aside, Dr. Thorp’s interests seemed to lean towards the stationery business. On August 13, 1889, US Patent 409,076 for a machine to fold leaves for books was issued to Elliott G. Thorp of Boston, MA (Thorp, 1889). He had been waiting for six years, as the application had been filed on October 31, 1883, while he was still with Winkley, Thorp, & Dresser, the diary manufacturer. A year later, U. S. Patent 423,836 was issued again to Elliott G. Thorp, for a “Scrap-Book” (Thorp, 1890). The application for that second patent was filed on November 29, 1889, suggesting that Thorp's creative juices continued to flow towards stationery in his newest business endeavors. So why establish a business primarily devoted to typewriters? It may have been that Dr. Thorp was again trying to assist his good friend Mr. Tilton, this time with a business in which Fred may have had a particular personal interest.

1889: Charles E. Tilton and his Typewriters

You may remember that Fred had a younger brother named Charles Edwin Tilton. While Charles' brothers were venturing into the world of stationery, Charles chose to become a jeweler and watchmaker in Worcester, MA (Cross, 1905). It so happens that watches have similar mechanisms to typewriters, and there is precedence for other jeweler/ watchmakers to have invented typewriters, such as John E. Molle, inventor of the Molle typewriter. On August 13, 1889, the same date that Thorp’s patent was granted, US Patent 409,128 was granted for a type-writing machine to one Mr. Charles E. Tilton of Worcester, MA. The patent was assigned to the Tilton Manufacturing Co. of Portland, ME (Tilton, 1889). So, we have a typewriter patent, assigned to a newly founded typewriter-focused company, invented by a watchmaker with the same name as a brother of one of the founding members of that same company. Coincidence? Perhaps, but it seems to me that this evidence suggests that Fred's brother, Charles Edwin Tilton, was the same Charles E. Tilton who invented the typewriter which was granted US Patent 409,128.

It is worth it to note that Robert Messenger has an alternative theory that one Mr. Charles Emery Tilton of Worcester, MA, also a jeweler, was the inventor, Charles E. Tilton. You are welcome to review his evidence at this link: https://oztypewriter.blogspot.com/2011/08/on-this-day-in-typewriter-history-lxxxv.html. It was actually Mr. Messenger’s blog that partially inspired me to dive into this research in the first place, as the mystery seemed too juicy to ignore, so I would like to thank him for the inspiration, and note that there were too many darn Charles E. Tiltons in the world at that time. Being partial to the coincidences I just laid out, I will assume that my theory is correct and proceed with the story.

So Fred G. Tilton’s personal interest to co-found a typewriter manufacturing company may have come from his brother who had invented a typewriter and who would have needed a way to market and manufacture it. You may have noted that one of the explicit purposes of the Tilton Mfg. Co. was to purchase patents; Charles' application had been filed five years earlier on December 19, 1884, so it would have been pending approval when the company was founded. Interestingly, a week after his patent was granted, on August 20, 1889, US Patent 409,289 for a printing mechanism for typewriting machines was granted to Arthur Irving Jacobs of Hartford, CT, which was also assigned to the Tilton Mfg. Co. of Portland, ME (Jacobs, 1889). Jacobs applied for the patent on October 16, 1888, after the Tilton Mfg. Co. was up and running, so it seems possible that the company had reached out to Mr. Jacobs for assistance with designing an improvement to Charles’ machine, perhaps to make it more marketable, and then also purchased Jacobs' patent under the rights of their newly founded company. It’s equally possible that the Tilton brothers simply liked the appearance of his design and decided to use it with their own invention to make the perfect index typewriter.

Arthur Irving Jacobs, known today primarily for his Jacobs drill chuck invented in 1902, had worked in both textiles and stationery early in his career. After learning the mechanical trade from his father, his first external job was with the Knowles Loom Works in Worcester, MA (Vintage Machinery, 2019). Given that Charles Tilton was also living in Worcester while Jacobs was there, and that Charles’ father was originally a wool manufacturer, it is possible that the two men knew each other before Arthur assigned his patent to Tilton. While working for Knowles, he invented a book-sewing machine, in which the Smyth Mfg. Co. of Hartford, CT, took an interest. Smyth purchased the patent and invited him to come work for them in Hartford. Jacobs left in 1887, and invented machines for book binding while working for Smyth until 1901 (Vintage Machinery, 2019). Sometime between Worcester and Hartford must have been when Jacobs invented the printing mechanism for typewriters that he then assigned to the Tilton Mfg. Co.

So, we have identified and provided some background on the inventors of the first typewriter patents that were purchased by the Tilton Mfg. Co., and the relationship between Charles Tilton and the company, but which typewriter had been invented, improved, and then sold by Tilton? If you guessed the Victor index, then you would be correct. Although the pictures in Tilton's patent do not look much like the Victor index, the typewriter has painted on its body two patent dates, August 13, 1889, and August 20, 1889, which match the two patents mentioned above, and the descriptions of the two patents match the operation of the typewriter. If you knew nothing else of the Victor index, then likely we could stop there; however, multiple sources reference different names as the inventors of this typewriter, creating a bit of a puzzle. Some sources indicate that the inventors were Messrs. Taylor and White, while others indicate that it was Arthur I. Jacobs alone who invented the machine. Even Typewriter Gazette had displayed Jacobs as the inventor for a time; this error has now been corrected. Robert Messenger noted that the inventor of the Victor index has been a riddle in the typewriter world for some time (Messenger (b), 2011). But why, when the evidence seems so clear that it was Charles E. Tilton who had invented the machine?

It seems to have started with the famous 50th anniversary issue of Typewriter Topics. In the issue, the Victor is said to be “. . . the devising of F. D. Taylor and F. A. White . . .” (Victor, 1923, p. 142). Later, neither Russo nor Adler, authorities in the typewriter world, correctly attribute the inventors, writing that it was F. D. Taylor and J. A. White who were responsible (Russo, 2002; Adler, 1997). Russo does indicate that A. I. Jacobs’ patent was an improvement to the machine, and Adler claims that these men are “responsible” for the machine rather than the inventors, but one can see where the confusion could have arisen for later historians. What I found surprising was that neither had mentioned Tilton at all, even though Charles shared his last name with the company to which both his and Jacobs’ patents were assigned. As Messenger points out, Taylor and White were both witnesses on Jacob’s patent (Jacobs, 1889), but even Messenger focuses only on Jacobs’ improvement patent for the Victor as he tried to unravel this tangled mess. I will recognize that Jacobs patented the most recognizable feature on the Victor index, the daisy wheel typing mechanism, so it’s not completely unfair to call him the inventor of the Victor; however, Jacobs' patent was not for the main mechanism of the machine.

It was on the website of the Smithsonian Institute (si.edu, n.d.) where I originally discovered that there are actually two patents listed on the machine (and then of course ran to check my own machine for this overlooked detail). The Smithsonian correctly attributes both inventors, and it was only after I read and re-read both patents that it became clear that the true inventor of the Victor index was Charles E. Tilton. While finalizing the research for this article, it was quite satisfying to come across one other source that correctly indicates that both C. E. Tilton and A. I. Jacobs were the inventors of the Victor index. I’ve copied that reference here to set the record straight (Adams, 1895).

Well, that seems clear enough, but with all the confusion in the literature, including from sources that are considered typewriter authorities, I felt the need to re-check all the evidence to make sure that I would not mislead the public in pronouncing Charles E. Tilton as the true inventor of the Victor index, so I turned to the patents marked on the machine. It should already be clear that Tilton and Jacobs were the original inventors of those patents since Taylor and White were mere witnesses, so the question was whether one or both men should be attributed. Upon review of the titles, it was Charles’ patent that named a “Type-Writing Machine”, while Arthur’s patent was only for the “Printing Mechanism for Type-Writing Machines”, again, fairly clear, but the design is still a pretty big feature of the machine. It was within the body of the patents where I discovered the origin of the machine itself, and with the origin, decided to pronounce one inventor. Within his Type-Writing Machine patent, Charles had listed a previous patent as a precursor to the claims made therein: U. S. Patent 306,295, granted August 4, 1883, of which he was also the inventor (Tilton, 1884).

This precursor machine’s patent was also for a “Type-Writing Machine”, but that seems to have been a somewhat loose interpretation. In an interview with Charles Tilton by The Phonographic World, he reveals that this predecessor was actually a shorthand machine, referred today by some as the Tilton Typewriter (Fudacz, n.d.). It was designed to be used with a new method of shorthand that Charles himself had designed (Tilton, 1885). Sadly, it appears that neither his shorthand system nor his first machine caught on, but in the interview Mr. Tilton mentions that he was working on a second machine. That second machine was likely what was to become the Victor index. The timing of the interview coincides with the application filing date for U. S. Patent 409,128. In the interview, Charles stated that he wanted to sell this second machine for $20, only $5 more than the original selling price of the Victor, and claimed that it would be as good as the Hall index typewriter, an indication that the new typewriter was also to be an index machine (Tilton, 1885). The fact that his own idea was the precursor to the Victor, and that The Phonographic World captures him talking about what was likely to become the Victor, lend proof to the theory that the Victor index typewriter really was the brainchild of Charles E. Tilton. I believe it is he who should be named in the history books as its inventor.

It was sad to realize that any excitement that Charles may have felt when his brother told him that he could finally market his own invention through Tilton Mfg. Co. would have been mixed with sorrow. Charles Edwin Tilton’s wife, Jennie Wedge, passed away at the tender age of 28 on June 26, 1888, just a couple of months before the Tilton Mfg. Co. had incorporated (Bob L., 2022). The two had wed on April 7, 1881, in Worcester, MA, the year after his brother Fred had a son, while Fred was still working at Lewis Merriam & Company, and the year that his other brother Frank had purchased Orson Dalrymple’s news and stationery store. Charles and Jennie had a daughter together, Winifred May, on June 2, 1882 (Bob L., 2022). Those seven years in Worcester that they spent together would have been when Charles was working on his new shorthand method and the patent for the Victor index. But after the pain would again spring joy. Two years after Jennie passed away, Charles married his second wife, Fannie L. Clapp, on May 21, 1890, in Waltham, MA (MA State Vital Records, 1890). About a year later, they too had a daughter together, Mildred E. (U.S. Census Bureau, 1910).

1888: Patent Assigned to Fred G. Tilton

It wasn’t just Fred’s brother or Aurthur Jacobs who assigned patents to Tilton Mfg. Co. and its directors. On May 1, 1888, three months before the Tilton Mfg. Co. was incorporated, Juan de la Cruz Escobár of Matanzas, Cuba, who was temporarily residing in South Bethlehem, PA, assigned his U. S. Patent 382,146 to Fred G. Tilton of Newark, NJ (Escobár, 1888). The patent was for improvements on a typewriter such that the formerly single-case machine could be made into a double-case machine, i.e., one could type using upper and lower case letters. Sr. Escobár indicated that the improvements were to be used with a typewriter that had been assigned U. S. Patent 350,717. In other words, this improvement patent was specifically designed for the beautiful World index typewriter, invented by Mr. John Becker of Boston, MA (Becker, 1886). Becker had previously assigned his patent to the World Type Writer Company of Portland, ME, on October 12, 1886.

You can't imagine the excitement when I came across this information! While cleaning the Victor and World index typewriters one day, my husband had pointed out that the two typewriters appeared to share a few parts. The platen seemed to be the same model on each machine, the size of the paper combs differed by only a few millimeters and had the same distinctive shapes, and the mechanisms that moved the comb back and forth were exactly the same in dimension and appearance. We wondered at the time if the two companies sourced from the same supplier, or if they shared any other links. Upon review of the famous Typewriter Database, Ted Munk said of the Victor index, “Manufactured by the Tilton Mfg. Co., Boston, MA. Similar to the World typewriter, but no connection is known other than both being made in Boston.” (Munk, 2017). And that’s where we left it. Here, several years later, we can now add to the annals of typewriter history a solid link between the two typewriters: the World typewriter had an improvement patent assigned to Fred G. Tilton, who was the soon-to-be co-founder and treasurer of the Tilton Mfg. Co., the company that sold the Victor index typewriter.

But why did this seemingly random inventor assign a patent for an improvement to a typewriter that was not his own to this seemingly unrelated man, Fred G. Tilton? Diving once again into the phone books yielded the answer. According to the 1888 edition of Trow’s New York directory of corporations (Trow (a), 1888, p. 238), the same year the Tilton Mfg. Co. was incorporated in Maine, Mr. Fred G. Tilton was listed as the treasurer of yet another company: the World Typewriter Company of 317 Broadway, New York. And the president of the establishment? You guessed it, our very own, Dr. Elliott G. Thorp (Trow (a), 1888, p. 238; Trow (b), 1889, p. 2171)!

1886-1894: The World Type Writer Company

With this exciting realization, let's take a brief hiatus from Tilton's story to explore the background of the World Typewriter Co., and the history of its beautiful typewriter, one of my favorites in our collection. On August 19, 1886, the World Type Writer Co. was formed in the state of Maine “for the purpose of manufacturing and selling type writers” (New Corporations, 1886, p. 1; Business Corporations, 1887). The original directors were President E. G. Thorp, Treasurer J. E. Spears, and Hiram Knowlton. These names should sound familiar: J. E. Spears was the name of the secretary of the Thorp Mfg. Co. in 1884, and there was a director W. J. Knowlton of the Tilton Mfg. Co. in 1888. By 1888, Fred Tilton was listed as the treasurer, so Spears must have handed over the role at some point. Considering the timing of the assignment of the improvement patent, I wonder if that had anything to do with the change in officers? Of course, the reverse may also be true, and Tilton may have been assigned the patent because he was the treasurer of the company. Or perhaps one had nothing to do with the other; research for another day . . .

Like many other typewriter companies, the World Typewriter Co. had multiple address listings. It was formed in Maine (New Corporations, 1886), and listed there as per Becker’s patent (Becker, 1886), was listed in Boston as per the Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition (World Typewriter Co., 1888), and was listed in New York as per the New York City directory (Trow (b), 1888, p. 2153). According to initial advertisements of the World (American Mag Pub Co., 1888; World Typewriter, 1887; World Typewriter, 1888) and Trow’s directory of corporations (Trow (b), 1889, p. 2171), it appears that the first main sales office was located at 30 Great Jones St., New York.

30 Great Jones St. also happened to be the office of George Becker, the original selling agent of the World typewriter (Dewey, 1887). Does that name sound familiar? Looking again into the Trow directory of 1888, we discover that John Becker, inventor of the World index, and George Becker, the initial selling agent of the World index, were indeed directly related through George Becker & Co. (both George and John were named in the directory), which was also listed at 30 Gt. Jones (Trow (a), 1888, p. 18). George Becker seems to have had a direct hand in the development of the World index; on February 14, 1888, George filed an improvement patent application for the machine listed in US Patent 350,717, i.e., the World, which was to add a less rigid inking surface and an automatic feed-roll rotating mechanism (Becker (a), 1891). On April 5, 1888, he filed another improvement patent application for an unspecified typewriter, but with drawings that had similar mechanisms to the World index (Becker (b), 1891). On July 16, 1888, he filed yet a third improvement patent application for again an unspecified typewriter that again had similar mechanisms to the World index. This third invention was co-authored with his business partner and the original inventor of the World index typewriter, John Becker (Becker & Becker, 1891).

Interestingly, but not surprisingly, those were not the only businesses associated with 30 Gt. Jones. Trow’s 1888 and 1889 directories also list: “Becker Brothers (engravers) (Philip & George Becker) 30 Gt. Jones” (Trow (a), 1888, p. 19; Trow (a), 1889, p. 24; Trow (b), 1889, p. 120). Philip and George ran Becker Brothers out of 30 Great Jones St., New York, at least through January 1893 (Becker Bros., 1893). At this point, it seemed safe to assume that all three Beckers, George, John, and Philip, were not just business partners, but were also brothers. Philip, too, had a link to typewriters, not just to the stationery world. As Robert Messenger pointed out, Analdo M. English assigned his patent for the Simplex typewriter, which was likely based on the design of the World typewriter, to Philip Becker (Messenger (a), 2011; English, 1892). I recommend Robert Messenger’s article if you are interested in the story of the Simplex typewriter and how it links to the World index and to the Becker brothers: https://oztypewriter.blogspot.com/2011/06/wonderfully-complicated-world-of.html

So, what of the World typewriter? Three years after the World Typewriter Co. was founded, an 1889 advertisement revealed that a new company wanted a piece of the action. The well known manufacturer of Columbia Cycles, Pope Mfg. Co., advertised that one could purchase the machine from their typewriter department (Masson & Bates (a), 1889).

A month later, the same magazine featured an article about the World:

“This typewriter was invented about two years and a half ago by Mr. John Becker. It was then, of course, in a very crude state compared with the perfected machine of to-day. Its success from the start has been phenomenal, and nearly fifty thousand of them are now in use in the United States alone. The machine of today is the result of practical ideas, experiments and improvements on the original acceptable machine. . . . This machine is called the World Typewriter, and is made in two styles: Single case, writing forty-four characters, and double case, writing seventy seven characters . . . A catalogue will be sent free to anyone addressing the Pope Manufacturing Co., Boston, New York and Chicago.” (Masson & Bates (b), 1889, p. 74)

Some of those experiments and improvements must have been related to George and John Becker’s 1888 patent applications, which were all granted in 1891, and which were all assigned to the Pope Mfg. Co. of Boston, MA (Becker (a), 1891; Becker (b), 1891; Becker & Becker, 1891). The other selling point, which may have been a key differentiator from the Simplex typewriter, the ability for one to be able to purchase either a single or a double-case machine, must have come from Juan de la Cruz Escobár’s patent (Escobár, 1888). As Tilton Mfg. Co. was in the business of buying and selling patents, the World Typewriter Co., under the watchful eyes of Thorp and Tilton, seemed to have capitalized on this knowledge to sell, or perhaps to license the patent for the improved World to its new manufacturing company. You may note in Becker’s improvement patents that the assignments were made via mesne assignments, which leaves the possibility that Tilton Mfg. Co. was involved in the sales of the patent. That said, I acknowledge that this is more of a hypothesis than a theory as there is little to no proof. In any case, it seems that Tilton and Thorp decided that one typewriter business and/ or sales of one index machine, the Victor, was sufficient, and let the World go to a different company. Perhaps the World had too many links to the Becker family, and they decided to sell to a high bidder, which seems to have been the Pope Mfg. Co.

It was fun to find the Victor, sold by Tilton Mfg. Co., and the World, sold by Pope Mfg. Co., advertised on the same page of the August 1889 issue of American Stationer, revealing the order winner for each of the machines: the Victor is advertised as cheap, while the World is advertised as simple (American Stationer, 1889, pp. 419-420).

Meanwhile, George Becker & Co. of 30 Gt. Jones was listed as “dissolved” in 1889 (Trow (a), 1889, p. 24), suggesting that John Becker, the inventor of the World index, decided to go on to pursue other lines of business. The World was left in the capable hands of Pope Mfg. for the time being, but it is clear that Pope had already initiated a relationship with the Typewriter Improvement Co. of Boston, MA in 1889. While some of the ads in 1889 reveal the manufacturer as Pope Mfg. Co., which had offices at 77 Franklin, Boston (Boston Almanac, 1891, p. 512), as early as April 1889, the Typewriter Improvement Co., located at 4 P. O. Square, Boston, MA, was listed as the selling agent for the World index (World Typewriter (a), 1889; World Typewriter (b), 1889). In February 1891, The American Stationer announced: “The Pope Manufacturing Company has sold its “World” typewriter and business connected therewith to the Typewriter Improvement Company, of (Boston), which company will hereafter be the sole selling agent of the “World” typewriter.” (Boston, 1891, p. 310).

An 1892 book called Boston: Its Commerce, Finance and Literature nicely summarizes the history of the World index:

“. . . The “World” is manufactured by the Typewriter Improvement Co., of this city, . . . The first patent on this device was issued to the inventor, Mr. John Becker, October 12, 1886. Later on, in the same year, he sold out to the World Typewriter Company, who, in turn, disposed of the property to the Pope Mfg. Co., and on January 7, 1891, the invention was purchased by the Typewriter Improvement Co., who were incorporated under the State laws of Maine . . . They also purchased from Mr. Becker the Canadian patents on the invention. . . . In addition to handling the World Typewriter the Typewriter Improvement Co. also buy and sell improvements in typewriters and aid typewriter inventors. . . .” (Parsons, 1892, pg. 251)

I hadn’t come across this summary until my main research had already been complete, so it was really rewarding to be able to find a source that directly confirmed the research!

The Typewriter Improvement Company started selling the machine as the New World Typewriter, as in the advertisement below from The Manufacturer and Builder (New World Typewriter, 1892; New “World” Typewriter, 1893). It was hard to tell whether any further improvements were actually made. The improvements to the typewriter that were patented in 1891 were likely already being used, and since this was the third time the selling and/ or manufacturing rights were traded, it is likely that this last company would have tried to capitalize without putting in too many resources; the machine was reaching the end of its lifecycle. There was a World Typewriter for the blind advertised by the Typewriter Improvement Co., which may or may not have been previously available (Typewriter Improvement Co., 1893), but that could have been invented long before even if this was the first time it was coming to market. Come 1894, the Typewriter Improvement Company started leasing the machine (Typewriters Etc., 1894; Typewriters Etc., 1895), and advertisements started to look a lot like product end-of-life activities. See the ad above by Perry Mason & Co., which had reduced the price from $10 to $3.75 due to limited stock that they were likely trying to offload (Perry Mason & Co., 1894). It is about that time when the World index likely ended its life, but the machine still lives on in the households of those lucky few who have managed to obtain this beautiful machine!

Back to the Tilton Story

In Part III we encountered the origins of the Tilton Manufacturing Company, learned the identity of Mr. Charles E. Tilton of the Tilton shorthand machine and the Victor index typewriter, discovered the link between Fred Tilton and the World and Victor index typewriters, and ended with a bonus, the history of the World index typewriter. Part III really was the outcome of years of research behind Discovering Tilton. In Part IV we will examine more of the inter-relationships between the various stationery businesses throughout this story, and will end with the final days of the esteemed Dr. Elliott G. Thorp, and his business partners and good friends, the Tilton brothers.

References

Due to the length of the reference list for this four part series, it has been posted separately. Please see the article titled "Discovering Tilton, References" for a complete list of all sources you will encounter in the text, and from which the pictures were pulled.

Comments